Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

How the ideas circulating among one noblewoman's coterie in 16th-century Dubrovnik anticipated modern feminist thought

https://aeon.co/essays/meet-the-proto-feminist-thinkers-of-16th-century-dubrovnik

Trsteno Arboretum near Dubrovnik in Croatia, established at the former home of the Gučetić/Gozze family. Photo by Gregor Noczinski/Flickr

On 6 April 1667, a powerful earthquake devastated Dubrovnik, claiming at least 3,000 lives and destroying most of the city’s buildings. Among the many losses were irreplaceable cultural treasures – thousands of books, manuscripts and archival materials. The Rector’s Palace, housing state records, was heavily damaged, and fires that followed the quake consumed much of what remained. Monastic libraries, particularly those of the Dominican and Franciscan friars, suffered great losses. Nobles also lost private collections as their residences collapsed. The disaster not only marked a turning point in the city’s urban and political history but also inflicted a deep scar on its intellectual heritage. If it were not for this earthquake, we would know more about a fascinating imbroglio that involved philosophy, politics and gender that happened in the 1580s and involved the city’s foremost noble families. Nevertheless, it’s still possible to piece together parts of the jigsaw from what has survived. What emerges reveals two remarkable women who dared to challenge the patriarchy using philosophical arguments in an age when such attempts could be counted on one hand.

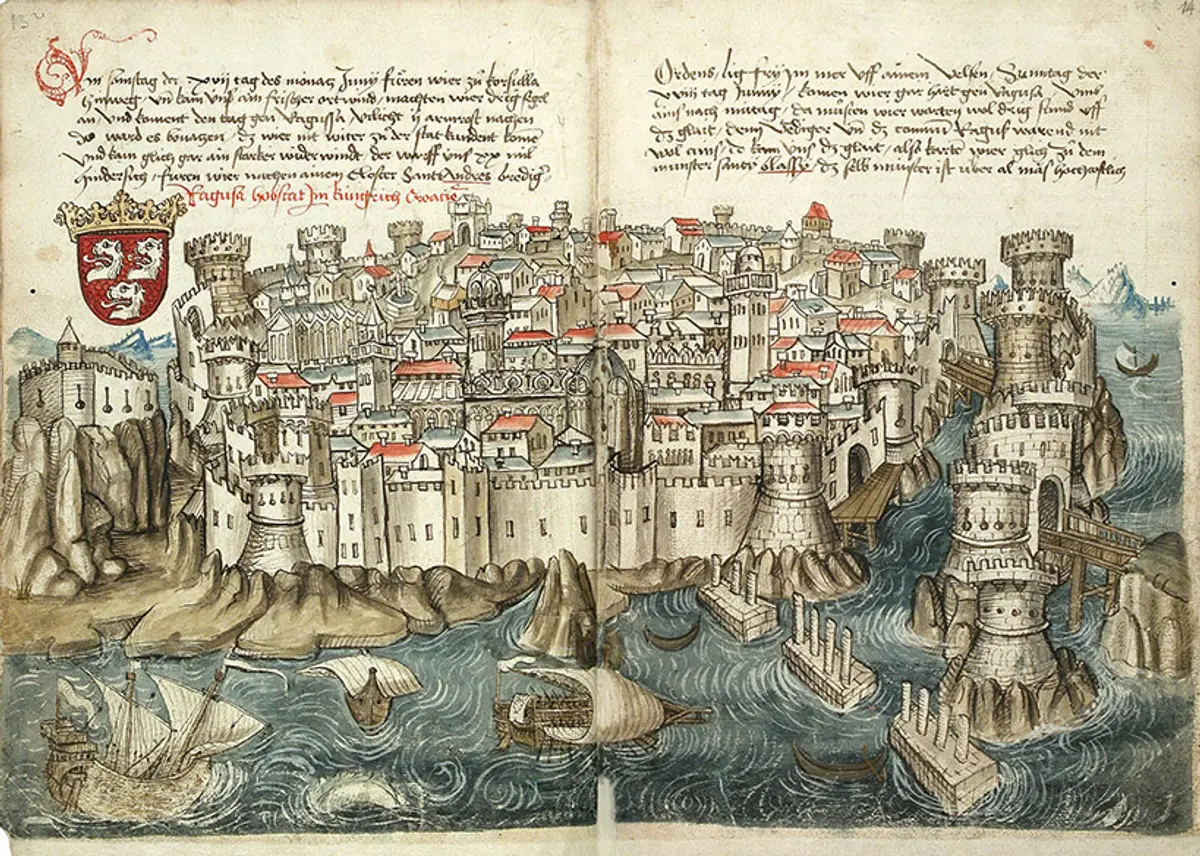

By the end of the 16th century, Dubrovnik boasted paved streets, an advanced sewage system, and a reliable water supply, innovations that placed it ahead of many other Adriatic ports in both functionality and sophistication. Its grand celebrations of St Blaise, the city’s patron saint, epitomised Dubrovnik’s cultural vibrancy, featuring theatrical performances, banquets, and public festivities that showcased its wealth and organisational prowess. To the outside world, the Republic of Dubrovnik projected an image of modernity and sovereignty, underpinned by well-defined laws, respected judicial institutions, and formidable fortifications that symbolised its enduring strength. The Republic of Ragusa, as it was known in Italian and Latin, thrived as a maritime power and intellectual crossroads, blending Italian humanism, Croatian (Slavic) traditions and Ottoman influences. Its aristocracy cultivated a reputation for erudition, with towering figures like the acclaimed national poet Ivan Gundulić, the earlier-generation Renaissance playwright Marin Držić, and the scientist Marin Getaldić shaping its intellectual identity.

The nobility’s commercial acumen fuelled Dubrovnik’s prosperity. Patrician families invested in salt production, textile exports, silver and shipbuilding, leveraging their Ottoman trade capitulations to dominate overland Balkan routes as well as maritime liaison with Italy and beyond the Adriatic. This economic success funded public works, including the mid-15th-century aqueduct by Onofrio della Cava and the lazaretto quarantine system, which safeguarded the city from epidemics. Socially, the Republic enforced strict hierarchies: interclass marriages were discouraged by law, and sumptuary laws regulated dress to reinforce aristocratic prestige. Yet these measures coexisted with progressive policies, such as the abolition of slave-trade in 1416 (the law called it ‘shameful, evil, inhuman, and against all civility’) and the establishment of one of Europe’s oldest pharmacies in 1317, reflecting a blend of mercantile pragmatism and Renaissance humanism.

Dubrovnik depicted in 1486, from Konrad Grünenberg’s Beschreibung der Reise von Konstanz nach Jerusalem. Courtesy the Baden State Library

During the Renaissance, Dubrovnik emerged as a vital meeting point between East and West, uniquely blending Western Christian and Eastern Byzantine, and later Ottoman, influences in its culture, politics and trade. Its strategic location on the Adriatic made it the most important port of the Eastern Adriatic and a key mercantile and diplomatic intermediary between the Balkan hinterland and the Mediterranean world. In the 15th century, Dubrovnik became one of Venice’s main rivals, leveraging its exceptional diplomacy and trade networks to compete with the Venetian Republic, while maintaining independence through skilful negotiation with both Western and Eastern powers, including the Ottoman Empire.

snip

1 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

How the ideas circulating among one noblewoman's coterie in 16th-century Dubrovnik anticipated modern feminist thought (Original Post)

Celerity

Thursday

OP

biophile

(1,057 posts)1. Interesting! Yet the more things change, the more they stay the same

The patriarchy really hates educated and independent women 😏😑