Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumStudy: Modeling Runs Show 70% Chance Of Collapse Of Atlantic Conveyer Current If GHG Levels Continue To Rise

The collapse of a critical Atlantic current can no longer be considered a low-likelihood event, a study has concluded, making deep cuts to fossil fuel emissions even more urgent to avoid the catastrophic impact. The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (Amoc) is a major part of the global climate system. It brings sun-warmed tropical water to Europe and the Arctic, where it cools and sinks to form a deep return current. The Amoc was already known to be at its weakest in 1,600 years as a result of the climate crisis.

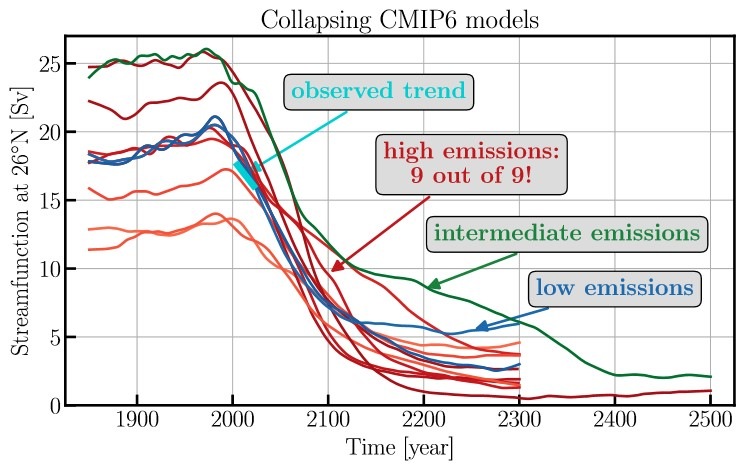

Climate models recently indicated that a collapse before 2100 was unlikely but the new analysis examined models that were run for longer, to 2300 and 2500. These show the tipping point that makes an Amoc shutdown inevitable is likely to be passed within a few decades, but that the collapse itself may not happen until 50 to 100 years later. The research found that if carbon emissions continued to rise, 70% of the model runs led to collapse, while an intermediate level of emissions resulted in collapse in 37% of the models. Even in the case of low future emissions, an Amoc shutdown happened in 25% of the models.

Scientists have warned previously that Amoc collapse must be avoided “at all costs”. It would shift the tropical rainfall belt on which many millions of people rely to grow their food, plunge western Europe into extreme cold winters and summer droughts, and add 50cm to already rising sea levels. The new results are “quite shocking, because I used to say that the chance of Amoc collapsing as a result of global warming was less than 10%”, said Prof Stefan Rahmstorf, at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, who was part of the study team. “Now even in a low-emission scenario, sticking to the Paris agreement, it looks like it may be more like 25%.

“These numbers are not very certain, but we are talking about a matter of risk assessment where even a 10% chance of an Amoc collapse would be far too high. We found that the tipping point where the shutdown becomes inevitable is probably in the next 10 to 20 years or so. That is quite a shocking finding as well and why we have to act really fast in cutting down emissions.”

EDIT

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/aug/28/collapse-critical-atlantic-current-amoc-no-longer-low-likelihood-study

FalloutShelter

(13,955 posts)“The Day After Tomorrow “?

Humans are a self fulfilling prophecy.

Are we not entertained?

NNadir

(36,849 posts)hatrack

(63,886 posts)the_liberal_grandpa

(251 posts)Read this book if you want to know the history of this current and just how quickly life on earth would change if it really stops (as it has done before)

The best book I have read on the history of climate on our planet.

OKIsItJustMe

(21,654 posts)28.08.2025 - Under high-emission scenarios, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a key system of ocean currents that also includes the Gulf Stream, could shut down after the year 2100. This is the conclusion of a new study, with contributions by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). The shutdown would cut the ocean’s northward heat supply, causing summer drying and severe winter extremes in northwestern Europe and shifts in tropical rainfall belts.

Time-evolution of the AMOC strength at 26°N (where it is observed) in the model simulations in which the AMOC shuts down. The short cyan line shows the observed trend of the observations for 2005-2023, the colour of the lines indicates the emission scenario that was used for the simulations. Graphic: Drijfhout et al.

“Most climate projections stop at 2100. But some of the standard models of the IPCC – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – have now run centuries into the future and show very worrying results,” says Sybren Drijfhout from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, the lead author of the study published in Environmental Research Letters. “The deep overturning in the northern Atlantic slows drastically by 2100 and completely shuts off thereafter in all high-emission scenarios, and even in some intermediate and low-emission scenarios. That shows the shutdown risk is more serious than many people realise.”

Collapse of deep convection in winter as the tipping point

The AMOC carries sun-warmed tropical water northward near the surface and sends colder, denser water back south at depth. This ocean “conveyor belt” helps keep Europe relatively mild and influences weather patterns worldwide. In the simulations, the tipping point that triggers the AMOC shutdown is a collapse of deep convection in winter in the Labrador, Irminger and Nordic Seas. Global heating reduces winter heat loss from the ocean, because the atmosphere is not cool enough. This starts to weaken the vertical mixing of ocean waters: The sea surface stays warmer and lighter, making it less prone to sinking and mixing with deeper waters. This weakens the AMOC, resulting in less warm, salty water flowing northward.

In northern regions, then, surface waters become cooler and less saline, and this reduced salinity makes the surface water even lighter and less likely to sink. This creates a self-reinforcing feedback loop, triggered by atmospheric warming but perpetuated by weakened currents and water desalination.

“In the simulations, the tipping point in key North Atlantic seas typically occurs in the next few decades, which is very concerning,” says Stefan Rahmstorf, Head of PIK’s Earth System Analysis research department and co-author of the study. After the tipping point the shutdown of the AMOC becomes inevitable due to a self-amplifying feedback. The heat released by the far North Atlantic then drops to less than 20 percent of the present amount, in some models almost to zero, according to the study.

Lead author Drijfhout adds that “recent observations in these deep convection regions already show a downward trend over the past five to ten years. It could be variability, but it is consistent with the models’ projections.”

…

DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/adfa3b

Frankly, the Low Emissions curve doesn’t look all that good…