Science

Related: About this forumDetermination of the Valuable Actinides Neptunium and Americium In Historically Operated Nuclear Reactors.

The paper to which I'll refer is more than 25 years old, and refers to nuclear reactors that operated in the 1990's in Japan, the United States and Germany, the latter before the Germans decided to kill people by switching from clean nuclear power to coal for reliable energy.

The paper is this one: Charlton, W. S., Stanbro, W. D., Perry, R. T., & Fearey, B. L. (1999). Comparisons of Calculated and Measured 237Np, 241Am, and 243Am Concentrations as a Function of the 240/239Pu Isotopic Ratio in Spent Fuel. Nuclear Technology, 1999, 128(3), 285–299.

The paper gives experimental insight to the accumulation of 237Np, 241Am, and 243Am during the operation of nuclear reactors. In reactors using the fast nuclear cycle, these isotopes would be important tools in denaturing weapons grade plutonium while recovering the embodied energy in them to slow the increasing rate of the atmosphere's deterioration.

In theory, albeit not in practice, one of these actinide isotopes, 237Np, could conceivably be used in nuclear weapons, although by use of the right separation technology, fluoride volatility, the potential for such abuse could be effectively eliminated by not separating it from plutonium via the use of uranium oxide exchange reactions (which would capture volatile hexafluorides of neptunium and plutonium by exchange reactions.) Transmuted into 238Pu, 237Np, would be an excellent tool for making plutonium of any grade, including weapons grade, unusable in nuclear weapons.

Being old, and from another time, the paper refers to these materials as "wastes" although I have convinced myself that put to use they can be utilized to recover energy while minimizing the potential for nuclear war, and in fact, be key materials for slowing, if not arresting, the acceleration of extreme global heating.

I do not have online access to the paper, but had it gifted to me by my son as a PDF, thus, in view of time, I can only excerpt limited text, but a few of the graphics are illustrative, both for the reassuring analysis of quality of reactor grade plutonium in what were then, typical burnups, as well as the concentration of americium and neptunium in the once through used nuclear fuels. The paper refers to computational codes available back then - obviously better codes are now available - and compares them with experimental analysis of the fuels via mass spectrometry and alpha spectrometry.

Some text about this motivation:

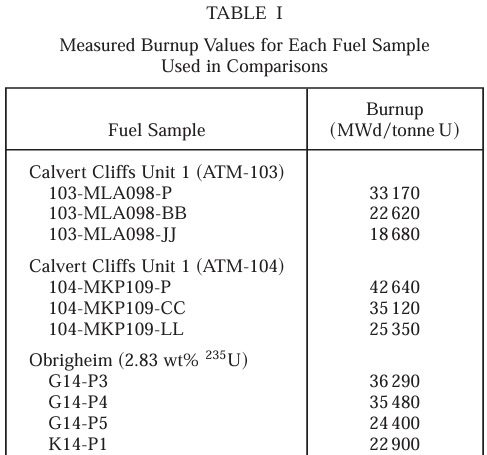

The reactors from which the used fuel was obtained are listed in the following table:

Mihama Unit 3 is in Japan; Obrigheim operated in Germany; Calvert Cliffs is in Maryland.

"Burn up" is a unit of energy efficiency of the fuel. The MWd is a derived unit of energy equal to 8.64 X 1010 Joules. A ton of sub-bituminous coal has about 2 X 1010 Joules. Thus at a burn up of 35,000 MWd, a ton of nuclear fuel is equivalent to roughly 150,000 tons of coal.

I cannot produce the many graphs in the paper, but a sample may be illustrative:

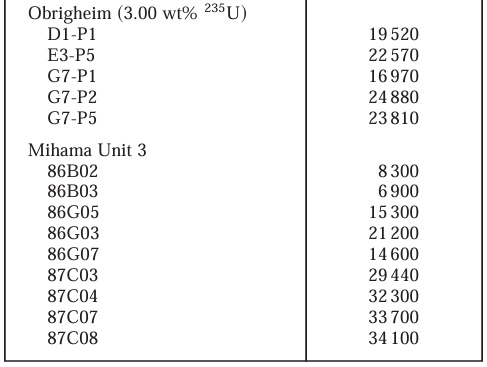

First of all, a sample 240Pu/239Pu Ratio at Calvert Cliffs:

This is somewhat higher than I would have guessed, almost 50% at high burnup. Note that the presence of other Pu isotopes 241Pu, 238Pu and 242Pu is not reported.

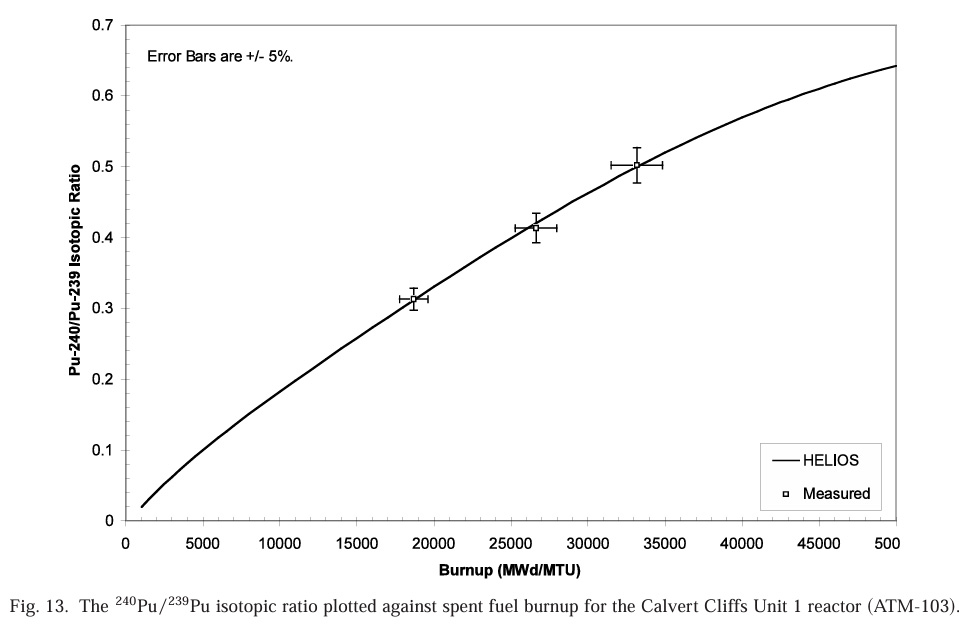

Accumulation of 237Np as a function of 240Pu/239Pu ratios:

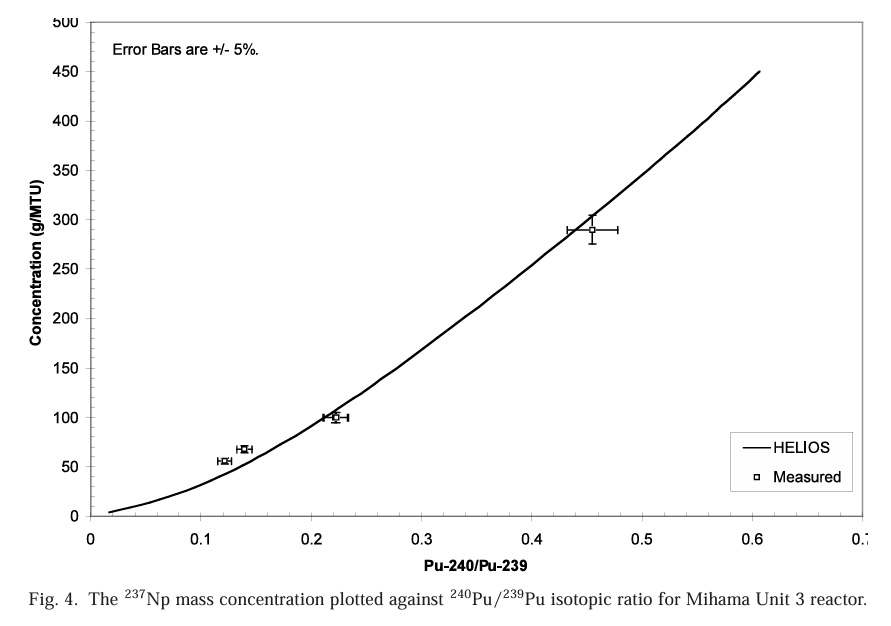

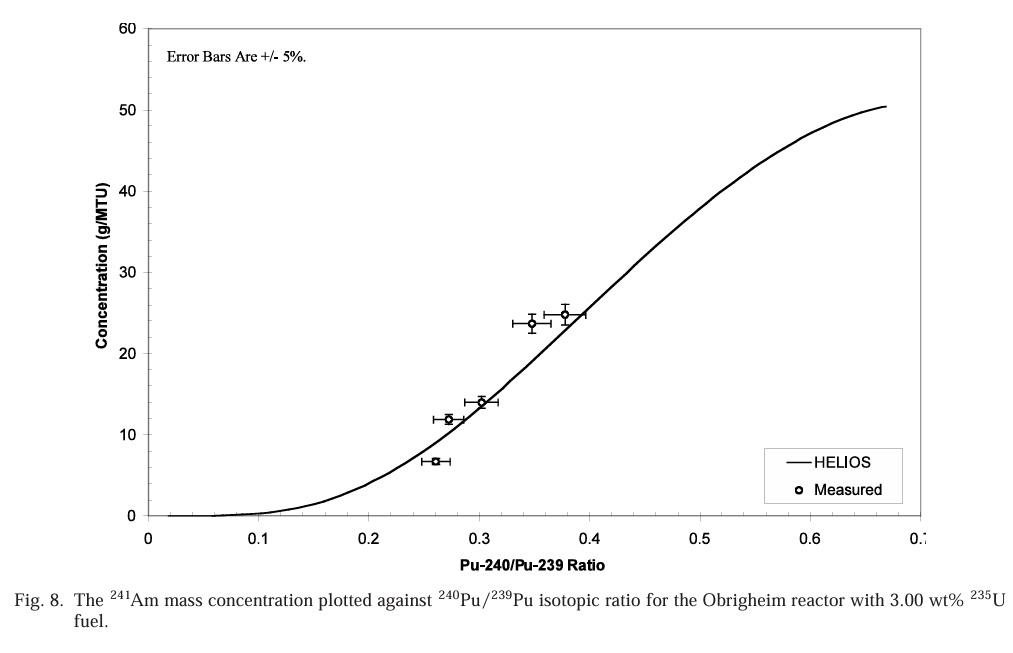

Accumulation of 241Am as a function of 240Pu/239Pu ratios:

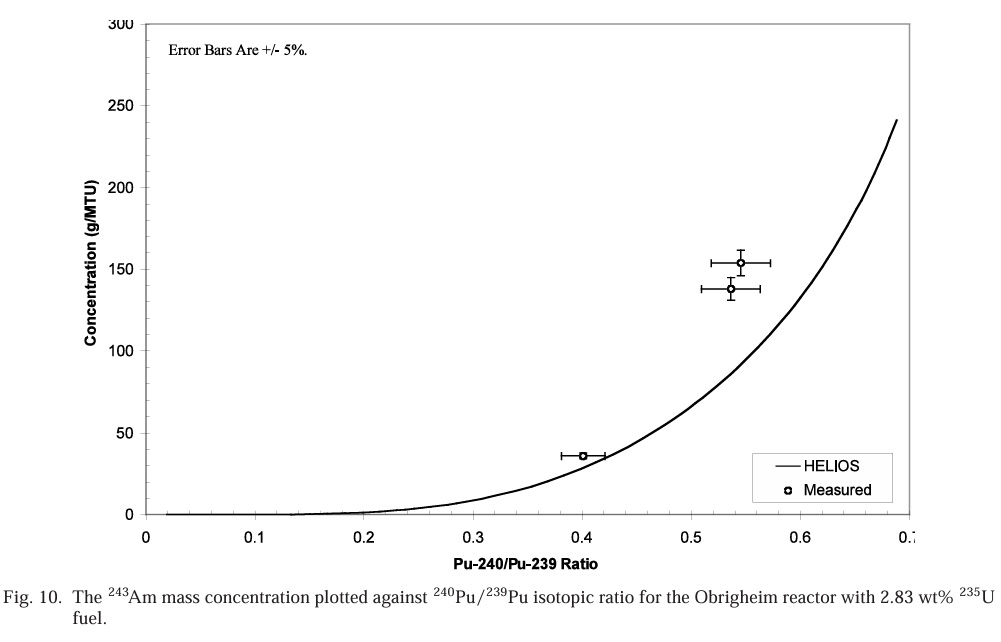

Accumulation of 243Am as a function of 240Pu/239Pu ratios:

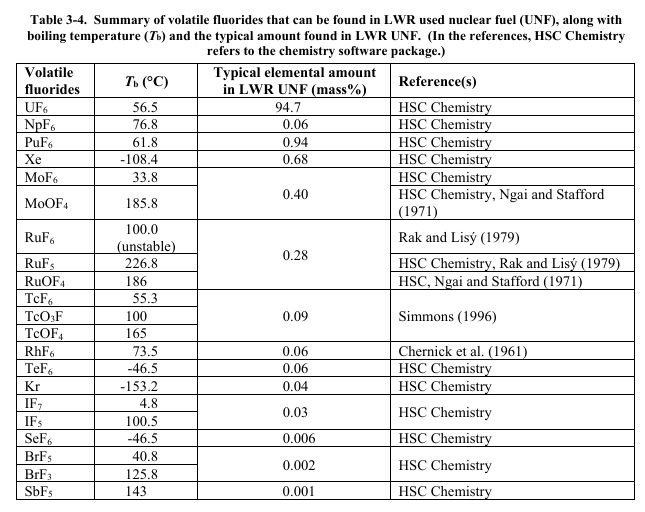

Note that these numbers are in grams per metric ton, meaning they are very dilute. However americium behaves like a lanthanide, and does not form volatile fluorides. As a rule of thumb, about 95% of used nuclear fuel is unreacted uranium, which does form volatile fluorides and is removed in the fluoride volatility process. Another 1% is roughly plutonium. These, along with neptunium will be removed from the fuel, as volatile fluorides, leaving a residue of americium, lanthanides, barium, cesium, rubidium and strontium fluorides. This would suggest that the americium quantities rather than being diluted in a ton of material might end up in 40 kg of residue, mostly fission products. As a practical matter however, the fluoride volatilization method actually removes a fair subset of fission products as volatile fluorides, including some very valuable precious metals and the noble gases xenon and krypton.

The elements subject to removal can be seen in the following table:

Source: Riley et al. Identification of Potential Waste Processing and Waste Form Options for Molten Salt Reactors PNNL-27723 (2018), Table 3-4.

The following calculation is very crude, inasmuch as it is not corrected for atomic weights, but assumes an "average" weight as a first approximation, to give a very loose "feel" for recovering americium:

The volatile fluoride compounds include those spanned by mass numbers 95 - 105 roughly, which a table of 235 fission yields suggests represents roughly 45% of the fission product residue. Mass numbers 82-85 will volatilize as krypton gas (including 85Kr, which is radioactive with a half-life on the order of 10 years, but which decays to stable rubidium) represent another 5% of this residue, and mass numbers 127 to 132, will be represented by the elements iodine or xenon, both of which will be removed, representing another 10% of the residue. So overall the remaining residue will be roughly 40% of 40 kg or 17 kg. Cesium isotopes, both the stable isotope 133Cs and the major radioactive isotope 137Cs, along with small amounts of 134Cs, and small amounts of 135Cs (suppressed because of the high neutron capture cross section of its short live precursor 135Xe] will represent about 12% of the 40 original kg. This material is not volatile except at very high temperatures, but it is soluble in water, as is rubidium fluoride, with the rubidium isotopes 85Rb and 87Rb, another 4%. The fluorides of these, cesium and rubidium, are soluble in water, so simply washing the residue with water will remove them, leaving us with something like 20-25% of the original 40 kg of residue, mostly consisting of the fluorides of strontium, barium, palladium, some indium and cadmium, and the light lanthanides (up to roughly gadolinium), 8 to 10 kg.

The point of this admittedly sloppy crude calculation, is that under these circumstances, the americium fluoride is relatively concentrated, a few hundred grams are now relatively easy to isolate using the many specialized procedures for separating lanthanides from their close chemical cousin americium, (and prehaps traces of curium).

If I've been glib - and arguably I have been so - what I have hoped to show is that it is indeed possible to recover americium from very dilute solid solutions, and, I believe, it's a good idea to do so, not because it's problematic as a "waste," but because - particularly because it has potential as a fuel.

The United States, despite being a country undergoing political collapse soon to be followed by economic collapse, by suicide, has, nevertheless, from its long golden age, a resource of around 80,000 tons of used nuclear fuel.

The further development of operational excellent in fuel burn ups since the 20th century, along with long periods for 241Pu to decay since fuels were removed in the 20th century suggests that there may be as much as 500 grams of americium in a ton of used nuclear fuel. This suggests that around 40 tons - again very, very, very, very crudely - are available.

That strikes me as enough to justify isolation, particularly if the valuable fission products are also isolated to defray any costs.

I have reported, about six years ago, on the critical masses of americium isotopes earlier in this space:

Critical Masses of the Three Accessible Americium Isotopes.

Americium as a fuel has some very interesting properties, only one of which is the ability to denature weapons grade plutonium.

This is, again, a very loose approximation, pure "back of the envelope" as they say, but worth, in my view, considering.

Have a pleasant week.