What if reality was against us? [View all]

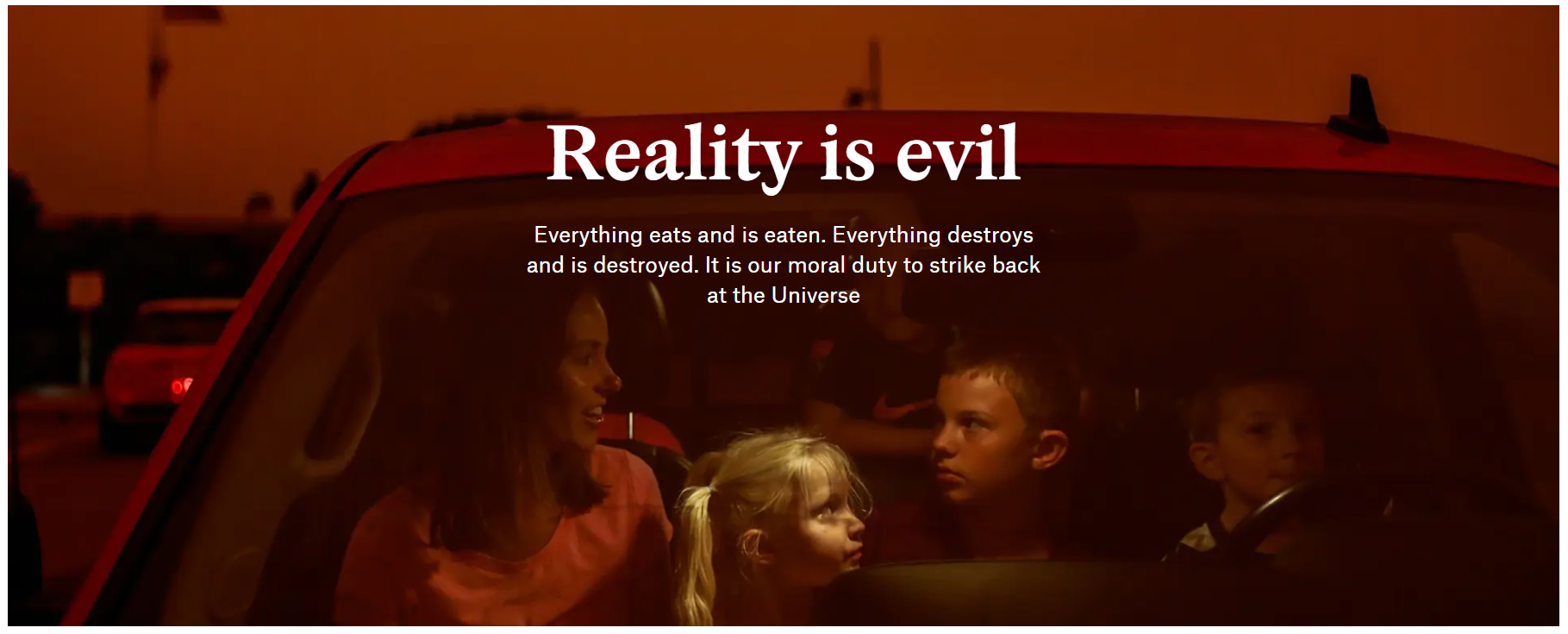

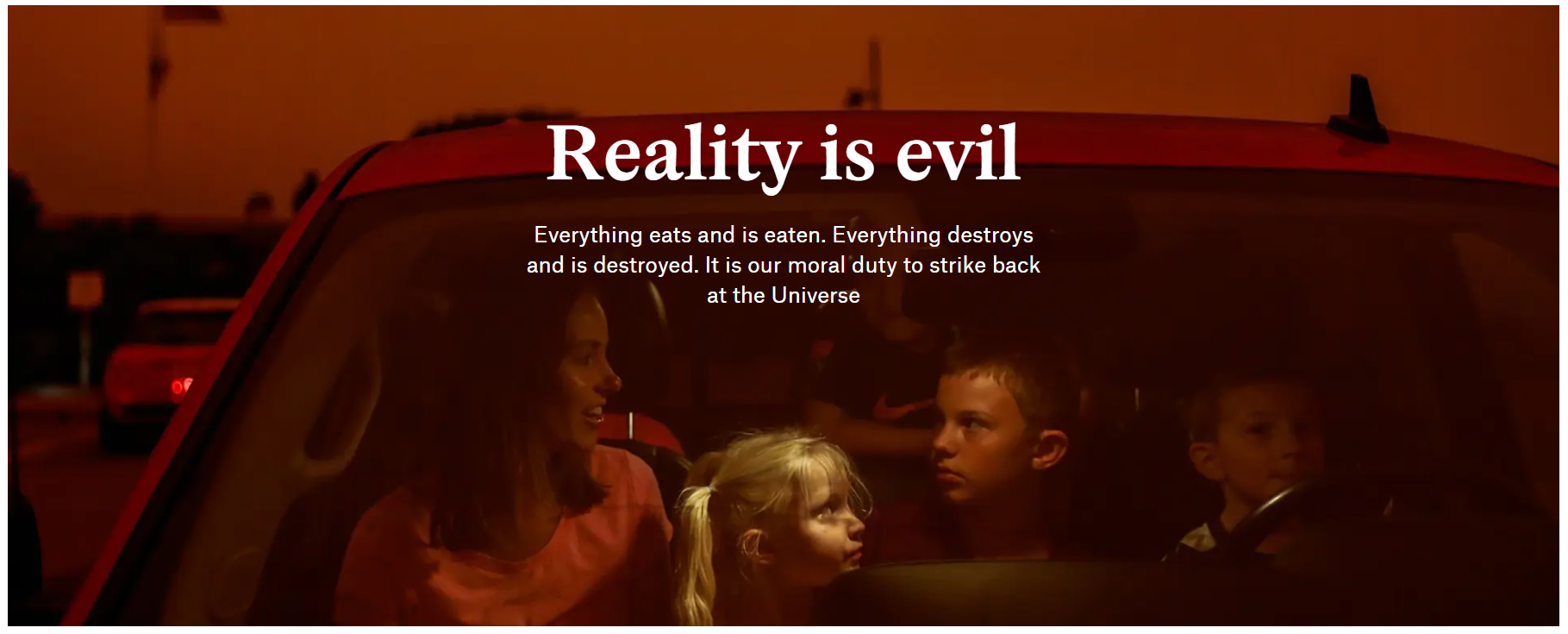

A road trip in Sausalito, California during wildfire season, 9 September 2020. Photo by Gabrielle Lurie/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty Images

https://aeon.co/essays/philosophers-must-reckon-with-the-meaning-of-thermodynamics

A road trip in Sausalito, California during wildfire season, 9 September 2020. Photo by Gabrielle Lurie/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty Images

https://aeon.co/essays/philosophers-must-reckon-with-the-meaning-of-thermodynamics

Reality is not what you think it is. It is not the foundation of our joyful flourishing. It is not an eternally renewing resource, nor something that would, were it not for our excessive intervention and reckless consumption, continue to harmoniously expand into the future. The truth is that reality is not nearly so benevolent. Like everything else that exists – stars, microbes, oil, dolphins, shadows, dust and cities – we are nothing more than cups destined to shatter endlessly through time until there is nothing left to break. This, according to the conclusions of scientists over the past two centuries, is the quiet horror that structures existence itself.

We might think this realisation belongs to the past – a closed chapter of 19th-century science – but we are still living through the consequences of the thermodynamic revolution. Just as the full metaphysical implications of the Copernican revolution took centuries to unfold, we have yet to fully grasp the philosophical and existential consequences of entropic decay. We have yet to conceive of reality as it truly is. Instead, philosophers cling to an ancient idea of the Universe in which everything keeps growing and flourishing. According to this view, existence is good. Reality is good.

But what would our metaphysics and ethics look like if we learned that reality was against us?

Apparently, life flourishes on Earth. Across the vast expanse of evolutionary time, living things seem to have veered toward greater complexity, diversity and abundance. Single-celled organisms gave rise to dense communities of bacteria. Trilobites evolved compound eyes with crystalline lenses of calcite. Animal brains split into two hemispheres, opening new frontiers of thought. Even after five mass extinctions swept the planet, life returned again and again, branching into countless variations of form and function in a ceaseless unfolding of renewal. When we look, we can find this ‘creativity’ all around us: in the weeds forcing their way through cracks in city pavements, in the scent of wet earth as fungi bloom, in the sound of children learning to speak.

Such accounts of life on Earth suggest there is a logic to all this change: the Universe is not static, but always

becoming, always moving toward new orders, new complexities, new forms of life and thought. This vision of reality as something generative – perpetually changing for the benefit and flourishing of all it creates – has dominated Western philosophy since its inception. It lies at the heart of our metaphysics (the speculative science of what it means to be), as well as our ethical intuitions and aesthetic ideals. Indeed, from Plato onwards, philosophers have generally agreed that living well means aligning with the rational order of the cosmos. ‘Live in accordance with nature,’ Marcus Aurelius urges in his

Meditations. For these thinkers,

nature serves as the ethical guide for our actions and the lodestone of our aesthetic ideals because it embodies something good.

snip