It's going to require an enormous courtroom.

Human rights groups will continue to look on helplessly.

~ ~ ~

Nayib Bukele shows how to dismantle a democracy and stay popular

Others will learn from El Salvador’s charismatic president

- click for image -

https://web.archive.org/web/20230728125040im_/https://www.economist.com/cdn-cgi/image/width=834,quality=80,format=auto/content-assets/images/20230722_AMD000.jpg

image: klawe rzeczy

Jul 20th 2023 | SONSONATE

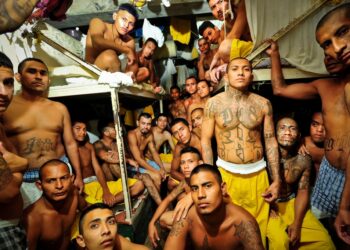

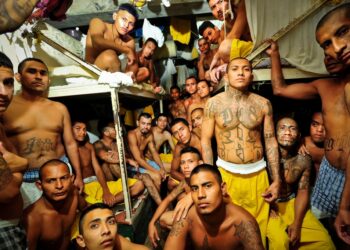

The gang crackdown began in earnest in March 2022, after 87 people were murdered in a single weekend, apparently after a deal between gangs and the government broke down. Mr Bukele declared a “state of exception” (ie, emergency). He let the police arrest anyone they suspected of gang ties, even if the only evidence was a tattoo or an anonymous tip-off. More than 71,000 people—a number equivalent to around 7% of male Salvadoreans aged 14-29—have been rounded up and tossed into overcrowded jails. Human-rights groups are outraged, but most Salvadoreans are delighted.

“Before, this neighbourhood was ruled by a gang, and you couldn’t leave it [without their permission],” says Miguel, a shop owner in Sonsonate, a small town 65km (40 miles) from the capital, San Salvador. Violence was routine. Three gangsters murdered Miguel’s sister because she broke off a relationship with one of them. Since Mr Bukele locked up the thugs, life has grown easier, he says. His murdered sister’s daughter, whom he adopted, can walk around without worrying.

The state of exception was supposed to last 30 days, but has been extended 15 times. Prisoners will eventually have trials, the government says, but so far they have had only pre-trial hearings, where dozens or even hundreds appear simultaneously before a judge, sometimes by video link. Whole batches are charged with “illicit association”. This need not mean belonging to a gang. It could mean knowingly receiving a “direct or indirect benefit” by having relations “of any nature” with one. Mr Bukele has raised the maximum sentence for “supporting” a gang from nine years to 45. El Salvador now locks up a higher share of its people than any other country.

Of those arrested so far, 6,000 have been released, says Gustavo Villatoro, the security minister. Asked if any more of the detainees might be innocent, he says the police and prosecutors are working hard “every day” to gather the necessary evidence to determine who is guilty. Trials (which have not yet started) will be concluded within two years, he says. He adds that the crackdown will continue until every last gang member is locked up: there are, he reckons, perhaps 15,000 more to catch, many of whom have fled from the country.

Tossing aside due process is an essential part of Mr Bukele’s strategy. Previously, when a gangster swaggered into a shop and demanded protection money, the owner knew that to refuse was to court death. He could call the police, but if he testified he would be murdered and if no one testified there would not be enough evidence to lock the gangster up.

Now, if a gangster swaggers down the street, anyone can get him locked up with an anonymous phone call. This completely changes the balance of power in previously gang-dominated neighbourhoods. “Before, the good people were afraid. Now, the bad people are,” says Miguel. (However, he asks that The Economist use a pseudonym.)

El Salvador’s homicide rate was already falling: from 106 per 100,000 people in 2015 to 51 in 2018 (the year before Mr Bukele was elected) and 18 in 2021 (before the state of exception began). Nonetheless, it is almost certain that the crackdown contributed to a further halving (see chart 1). El Salvador had eight murders per 100,000 people in 2022, a rate only slightly worse than in the United States.

. . .

Hard cell

When critics accuse Mr Bukele of flouting norms, he revels in his transgressions. For example, his government invests in cryptocurrency. The only public guide to how much it has bought is the president’s tweets. Sticklers for transparency complain. Mr Bukele boasts that he buys Bitcoin (with public money) on his phone, while in the toilet. He announces new policies via social media. State outlets amplify his message; paid trolls deride his critics, according to an investigation by Reuters. Amparo Marroquín of the University of Central America in San Salvador reckons that the president needs just 12 hours to have everyone talking about a topic. By contrast it takes the opposition 500 hours.

More:

https://web.archive.org/web/20230722122343/https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2023/07/20/nayib-bukele-shows-how-to-dismantle-a-democracy-and-stay-popular

= new reply since forum marked as read

= new reply since forum marked as read